Elizabeth A. Johnson ‘Quest for the Living God: Mapping the Frontiers in the Theology of God’ (Bloomsbury, 2011)

It was difficult to choose just one book by Elizabeth A. Johnson to review. She Who Is is a seminal text in Feminist Theology and her most recent work Listen to the Beasts ploughs a rich and exciting ecological furrow. Yet in the end it had to be Quest for the Living God. This book has not only sold a shed-load of copies but was also censured by the Bishops Congress of America for not ‘ground[ing] itself in Catholic theological tradition’ and, most ominously of all, threatening to lead the plebs astray with the use of ‘ambiguous’ ideas about female divinity (!). Johnson has invigorated religious and lay readers alike and offended the modern day Pharisees with this book and for these reasons alone it must be worth a look.

“If you have understood it, it is not God” St. Augustine

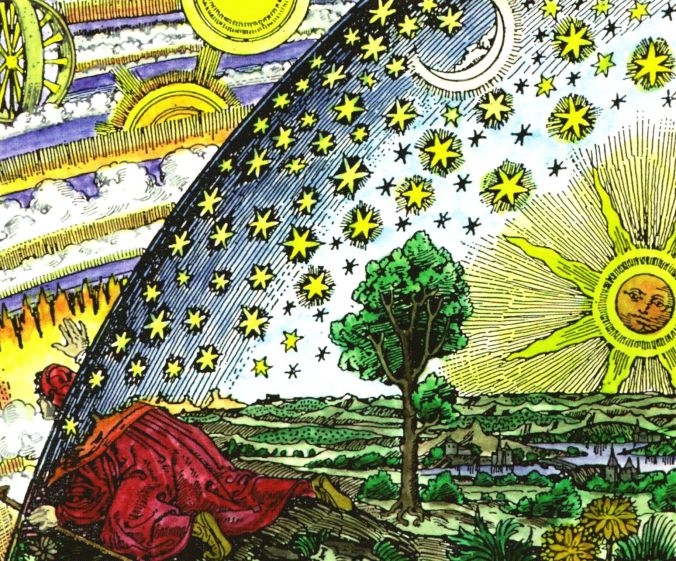

Johnson begins by defining her terms and in a pretty controversial way. For her the ‘Living God’ must by definition be anathema to the white-bearded male of the Enlightenment lording it over all the world. A God that can be understood in rationalistic, 18th Century terms in necessarily finite – it is finished, static and unchanging – and therefore cannot be God. Instead, Johnson posits the Living God of Christianity as present since the foundation of the world, completely beyond human comprehension, and her (God’s) essence and residue present in all humanity’s metaphysical encounters. By differentiating between mere ‘religions’ and the Living God, Johnson claims that ‘religions die when their lights fail… when their teachings no longer illuminate life as it is actually lived’ while the eternal Living God just hops on the next set of rituals and continues her good work. This is good news for spiritualists and those working on ecumenical endeavours but it is surely an intolerably post-modern watering-down of ‘the way, the truth and the life’ for orthodox Christians? The American bishops certainly thought so, but as Johnson continues I found a portrait of God much closer to my lived experience than old beardy.

In QftLG Johnson throws down the gauntlet to those who argue that by seeking any accommodation with the modern world our faith is fundamentally compromised. On the contrary, she argues that this static and personified God of guilt and punishment is already a compromise too far with an erroneous set of formerly modern ideas. For those still unsure she sums up ‘yes, the God of [18th Century] theism is dead’.

This book is a call for progressive Christians to turn the argument on its head. Far from apologising for risking its’ purity by taking our faith out into the world in a dialectical way, we should highlight the risk of faith’s destruction brought about by allowing it to become encrusted with dogma, ritual, prejudice and power relations. Johnson’s Living God is ineffable mystery, boundless truth, overflowing love and human beings are and have ‘always been drawn towards’ her. The question is will we follow them out into the world god so loved, or stay inside with the statutes and the statues. The law is not struck away though, and following the Living God doesn’t require loose morals and a tight man-bun but an engagement with the most radical readings of the Gospel currently on offer.

“The struggle against atheism is foremost a struggle against the inadequacy of our own theism” Karl Rahner

So God is with, through and in us then? So far, so good but where exactly does the Christ come into this Christianity? It turns out that he was out there in the world too.

QftLG provides overviews of a variety of bottom-up conceptions of Jesus, from familiar Latin American ones of a Jesus who lived and suffered with the poor to lesser-known “first world” situated readings. These vary from African-American to Latina/o to one from a group of Canadian housewives who radicalised their faith and their lives through identifying with Jesus as carer and nurturer, not just of one family or race but of the world. There isn’t room to go into them all here but the common thread is far from being a judge and never merely a model of good behaviour, Jesus is a companion and supporter of those on the road to justice. What affronts Jesus is not forgetting to say your prayers now and again but depriving humans of their dignity. Whether that takes the form of robbing indigenous people of their land in Brazil or by marginalising housewives in British Columbia, it is sure to get God’s dander up, and Jesus shows the path of resistance.

People with a legitimate grievance will naturally have a less saccharine reading of the Gospel than [good boy + death = sin free] and QftLG is an attempt to transport some of this reading into the spiritual lives of more comfortable Christians. The oppressed and marginalised hear Jesus preaching a love of God that is both unconditional and unsentimental; yes, any wicked man can become good but make no mistake, those who remain wicked must be opposed and they will be punished. The oppressed don’t see the meek, supplicant Jesus from TV too much either. They see a man who raged at injustice and stood up to those who perpetrated it, despite the inevitable cost. This is the man who is to be our model if we truly want to serve the Living God. Moreover, the cross ceases to be the site of the cosmic pay-off of children’s theology and becomes an amplifier for all the crosses set up in the world today, the ones that we find so easy to ignore. God suffered on this Earth like so many of its inhabitants suffer today, and by taking humans off their modern crosses – whether economic, social or personal – we live out the resurrection, that never-ending gift of hope and offer of life. That Johnson finds Christ outside with the downtrodden of all continents is bound to unnerve politicians, captains of industry and, I don’t know, bishops but it should make all of us with enough to live off and the correct residence permit ask a few tough questions too.

‘The highest blessing of all creation lies in the form of a woman’ Hildegard of Bingen

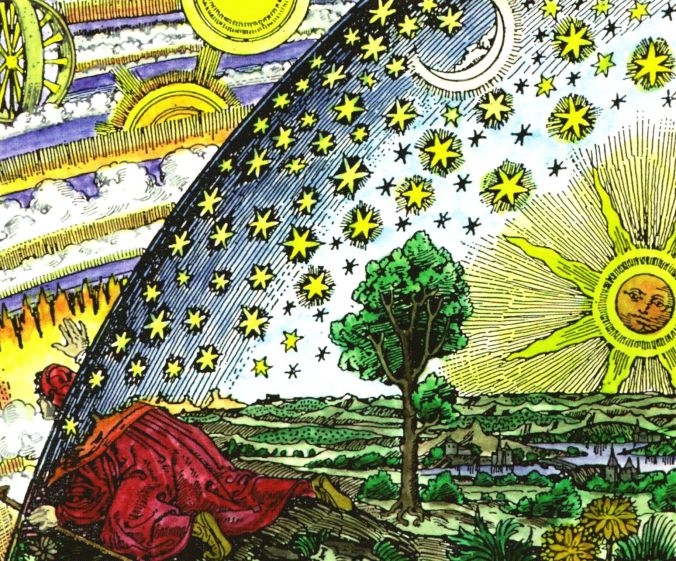

I wanted to write this final section on Johnson’s treatment of the femininity of God as it’s the part that has caused the most hullabaloo with those stout defenders of doctrine. Like the Jesus outlined above, Johnson’s Living God makes more radical demands on us in the here-and-now than you might expect. This isn’t just ‘God created everyone so he must be a bit of a she sometimes so ordain a few women yeah?’ revisionism. Johnson argues that women can’t be expected to step into patriarchal structures and conform to male archetypes, instead these structures (in both church and society) must be radically transformed to accommodate the needs and talents of the excluded half of humanity. Perhaps more shockingly (to some), she goes on that the all-male idea of God that exists in the church today is always hierarchical and oppressive, evoking king and father and being used to sustain both the patriarchal family and state. God has no masculine nature, and no feminine nature either, humans just find reflections of their own experiences in God, whose only nature is unending love and unknowable mystery. It’s necessary for us to find these because it’s the only way we can hang on to anything. For this reason images of God as female are necessary in the Church to offer another image of the living God that resonates with the female half of the congregation. Oh, and the sweetest part of Johnson’s argument? It’s not the least bit heretical. Beyond just the idea of female nature being creative and suckling the universe, cosmic-wombs etc. etc. Johnson uses scriptural sources and refers to the doctors of the Church to show that everything we consider Godly in the Christian tradition exists in feminine form. God is a true and wise guide for our Earthy pilgrimage? No problem, the God of the book of Proverbs is the feminine Sophia, translated as ‘wisdom’. God is a mighty fortress and smites the wicked? Sure she does, the Prophet Hosea has God referring to herself as a ‘mother bear’ who when ‘robbed of her cubs’ will find the guys who did it, ‘attack them and rip them open’ (Hos. 13:8). Also, consider what we know of women in this world. They can provide life-giving food for their children, so how exactly does a female God giving the sustaining gift of grace not function as a metaphor? A woman can provide for all her children equitably while running a household, so why does a metaphor of “God the Mother” apportioning cosmic justice fall so flat? This is the genius of Johnson’s argument. Like we saw with the nature of the Living God, she refuses to engage conservatism theism on its preferred ground. Instead she outlines a convincing, radical yet somehow familiar alternative (ie. a feminine deity) and asks ‘what exactly is the problem here?’ Her opponents shuffle their feet because there isn’t one.

‘Love has fallen on me, now I really see, love has fallen on me’ Chaka Khan

As you can probably tell, I loved this book, firstly because it was an interesting introduction to a lot of exciting new ideas about what it is to be a follower of Jesus Christ. Yet the most powerful thing was to see all these vibrant ideas next to each other in one book, different yet complimentary, collectively testifying to the truly infinite and universal nature of the Living God.

So finally, consider this: if God is neither male nor female, why should humans have to be? In the Living God we are offered a peek at the image we were created in, and it’s wet clay, a block of marble, a tabula rasa. God is everything, so we can be anything. Every trans-gender teenager ostracised by their church needs to know that they are closer to the image of God than any of us! God is gay and straight and black and white, there’s nothing unnatural in creation, sin is the result of the choices we make after the fact. The limitlessness of the Living God offers us the opportunity to experience doubt without guilt, not as a personality flaw but as a natural reaction to something we will never comprehend, but will always be there ready to accept us. Using scripture and modern theological thought Johnson shows a God we can never truly know but one a hell of a lot easier to love than a theistic thunderbolt-thrower. We are set free from the hard labour of self-flagelation and entrusted with the harder labour of trying to change a sinful world with the radical, transforming love of Christ. There is a Living God, we are here to quest for her and the deeper we get the further there is to go – this questing can’t help but change us and is an essential part of our nature. A static idea of yourself is as much an idol as a static idea of God. God changes as we learn more, and so should we. A world that gives us unchanging roles to play, in personal relationships, the family, our jobs and society at large, is trying to stunt our spiritual growth and shut down the quest for the living God – no matter how hard it seems, this is a world that needs to be changed.